Batteries are getting cheap. So why aren’t electric vehicles?

If the world has learned one thing from the adoption of wind, solar, and other green technologies over the past two decades, it’s this: Clean energy tends to get cheap as technology improves.

Since 2010, the cost of utility-scale solar power has declined by 82 percent; onshore wind has gone down by 39 percent. In many markets around the world, renewable energy is now cheaper than coal. The price of lithium-ion batteries has also plummeted: In 2011, a lithium-ion battery cost $946 per kilowatt-hour. Last year, it cost only $132.

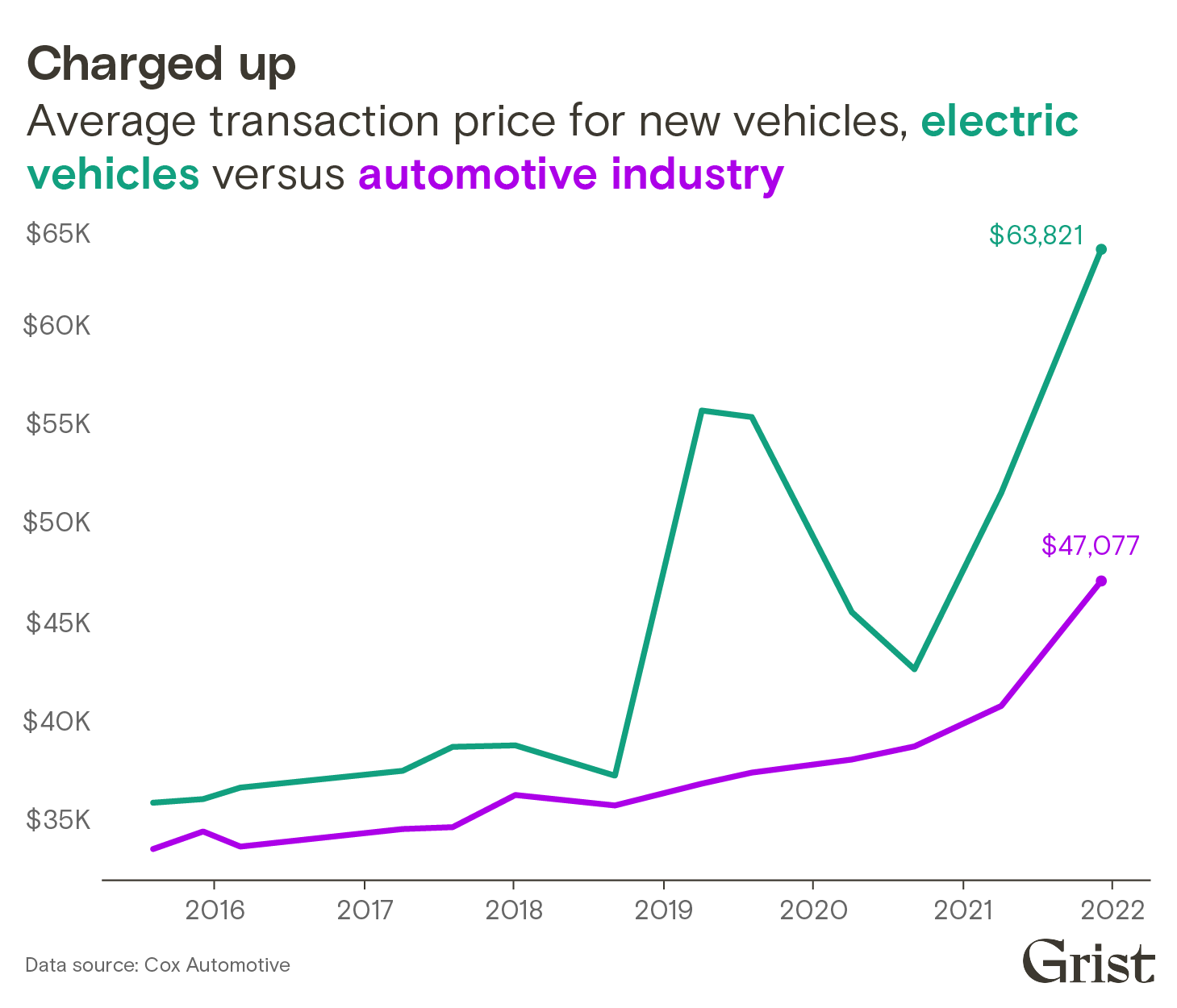

Electric cars have long been expected to follow the same trajectory. But even as batteries have gotten cheaper, the cost of purchasing a new electric car in the United States has skyrocketed. According to data from Cox Automotive, an automotive services firm, in 2015 the average price paid for a new electric car was $35,880 — not much higher than the industry average of $33,543. By last December, however, the average price of an EV had ballooned to $63,821, an almost 80 percent increase — while the average cost of a gas car was around $47,000.

For almost a decade, analysts of electric vehicles have whispered, analyzed, and projected a magic crossover point for EVs — “price parity,” or when electric cars will cost the same amount to produce as traditional, gas-powered cars. After that, if battery prices continue to fall, EVs would eventually cost even less than traditional cars. Analysts have long estimated that price parity would be reached when batteries cost less than $100 per kilowatt-hour. But even as battery prices inch toward that level, the magic crossover point seems further and further away.

“Battery prices are falling and that’s great,” said Scott Hardman, a researcher at the Institute for Transportation Studies at the University of California, Davis. “But when we look at the average starting price of a gas car and an electric car — they’re not getting closer. They’re diverging.”

For years, demand for electric cars grew steadily; but interest in EVs increased rapidly over the last few months, as gas prices rose and car companies rolled out new models. In the two-week period following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in March, online searches for new and used EVs nearly doubled. And by some metrics, EVs are already cheaper than gas-powered cars. According to an analysis by Consumer Reports, many electric cars turn out to be cheaper than gas-guzzling cars over the entire lifetime of the vehicle; after all, electric cars cost significantly less to “fill up” than gas cars and, with fewer moving parts, they also cost less to maintain.

But the sticker price of EVs continues to be higher than their gas counterparts — in some cases by a large margin. For example, the 2022 Hyundai Kona EV, a small electric SUV, starts at $32,000. The company’s gas-powered version, the 2022 Hyundai Kona, has a suggested retail price starting at $21,500. And research indicates that high up-front costs are a sticking point for many buyers. According to a recent survey from Cox Automotive, 51 percent of American consumers considered EVs “too expensive to seriously consider.” Morning Consult, a survey and research firm, similarly found that 47 percent of Americans said they weren’t willing to spend more to buy an EV. And, while some automakers still have the benefit of a federal tax credit for EVs — up to $7,500 off of a new car — the big players, like Tesla and General Motors, can no longer offer consumers the credit. (Manufacturers that have sold more than 200,000 electric cars are no longer eligible.)

So why have electric cars bucked the clean technology trend and gotten more expensive? Part of the reason is that cars generally have gotten pricier. As Nathaniel Bullard of the energy research firm BloombergNEF writes, “Inexpensive new cars have pretty much vanished in the U.S.” In 2012, more than half of new cars sold were priced under $30,000; in 2020, more than half of new cars were priced over $40,000. Inflation doesn’t fully explain this change: A $28,000 car in 2012 would only cost around $35,000 today. In the past two years, a semiconductor shortage and general supply chain problems have caused prices to spike even more.

But Hardman argues that doesn’t tell the whole story. According to a database of the make, model, and trim of every vehicle on the market in the U.S., the average cost of an EV model in 2014 was about $49,000, while gas-powered cars cost about $41,000 — a split of $8,000. Today, Hardman points out, an EV model costs on average $70,000, while a gas car costs about $48,000 — a bigger gap of $22,000.

Cheaper EVs do exist — just not in U.S. markets. In China, the average cost of an electric car is $24,000; in Europe, it’s $46,000. But American automakers appear to be taking a different approach, one inspired by Tesla’s rollout of its sleek, high-end Roadster. “Automakers will first roll out their big, range-topping, super pricey — kind of like their halo model,” DeGraff said, referring to a marketing term for a high-end car designed to bring consumers into the brand. “Then after they’ve collected the money for the bills, they can start dumping money into R&D for lower models.” General Motors, for example, has debuted the monstrous Hummer EV (from $109,000), and Ford has created an all-electric Mustang Mach-E (from $44,000).

Robby DeGraff, an industry analyst for AutoPacific, says that in some ways, automakers are just responding to the market. “Consumers right now are really, really hungry for crossovers,” he said, referring to the lighter, more fuel-efficient versions of SUVs. Since crossovers are often more expensive than compact cars or sedans, automakers can roll out EV crossovers — like Tesla’s $63,000 Model Y — and get a higher profit margin from them.

Car companies are also putting bigger and better batteries into their EVs, which contributes to higher prices, says Corey Cantor, an analyst at BloombergNEF. “Automakers have been focusing on range,” he explained. Nearly a decade ago, the best-selling fully electric car was the Nissan Leaf, a compact vehicle with a 24-kilowatt-hour battery, which provided a measly 84 miles in range. The 2022 Tesla Model 3, on the other hand, can carry a battery between 50 and 82 kilowatt-hours — for a range between 220 and 313 miles. “When you compare EVs today to EVs a decade ago, today’s EVs are killing it,” DeGraff said.

Whether EVs are closing in on price parity also depends on what the term means. According to data from Cox Automotive, electric cars are closing in on price parity with luxury vehicles — just not with the market overall. At the moment, the focus on expensive models may not be hurting adoption of EVs. The supply of EVs is so low — and demand so high — that some owners are selling their cars used for more than the original purchase price. Waitlists, such as that for the Ford F-150 Lightning, have reached hundreds of thousands of customers. With gas prices high, the demand for electric vehicles may outweigh the higher upfront price tag.

But President Joe Biden has called for 50 percent of new car sales to be electric by 2030. In some states, including California, governors have vowed to make all new car sales electric by 2030 or 2035. For that to happen, there will have to be a shift toward lower-cost vehicles. “At some point it has to change,” Hardman said. “If we’re gonna get like 100{e3fa8c93bbc40c5a69d9feca38dfe7b99f2900dad9038a568cd0f4101441c3f9} of car buyers to choose electric vehicles in California and other states it can’t, can’t continue.”