How to Buy a Car at a Fair PricWith the Ongoing Chip Shortage

You can blame 18-way power-adjustable seats. Or tabletlike 15-inch infotainment touchscreens. Or LED rear lighting. Or really, any of the 3,000-plus operations that tiny microprocessing semiconductor chips perform in a modern automobile. Because the massive demand for those chips, and the inability of carmakers to secure them from the companies that produce them, is making this one of the most difficult and costly times ever to purchase a vehicle.

These tiny but essential chips are the brains in our vehicles, and there simply aren’t enough of them right now. Industry experts state bluntly what car buyers have felt daily for the past two years: We are experiencing a chip shortage that is limiting automakers’ production capacity, increasing prices, and making it almost impossible, in some cases, to find an ideal vehicle on a dealer lot.

“The main effect is high, high, prices and low supply,” says Michelle Krebs, an executive analyst for Cox Automotive, a global automotive services and software company.

Buying a vehicle before the shortage was already a stressful endeavor, one that required assiduous shoppers to decipher complicated financing, avoid costly fees, and negotiate like an embattled world leader at a peace conference just to achieve a fair price. Now, thanks to the chip shortage and global production slowdown, the challenges of car buying are so great that Krebs says she’s heard of people flying to places hundreds of miles away where they can get a vehicle easier.

Worse, the experts we talked with don’t expect this problem to abate any time soon. Toyota, the world’s largest automaker, reported that its global production dropped by 40 percent in the fall of 2021 and hasn’t yet fully recovered. Honda sliced its manufacturing by about 30 percent during that time. Production at the Volkswagen Group, the largest carmaker in Europe, declined by nearly 35 percent. “Most automakers say it should improve by the second half of this year, but chip supply for autos won’t return to normal through 2023 and possibly 2024,” Krebs says.

If you’re shopping for a car, you will need to be resourceful to find a vehicle that meets your needs and budget. But even with your skill and guile, Brian Moody, executive editor at the car-shopping site Autotrader, says that for the foreseeable future, “you are going to be paying more.”

So buckle up. It’ll be a rough road to the vehicle of your dreams. The good news is that after nearly two years of shortages, several strategies and tactics have emerged to help you get the type of vehicle you want at a fair—though likely elevated—price. Understanding how we got here, and the factors affecting new vehicle price and availability, will help you deploy them effectively, with minimal stress.

The Tiny Chip Causing Big Problems

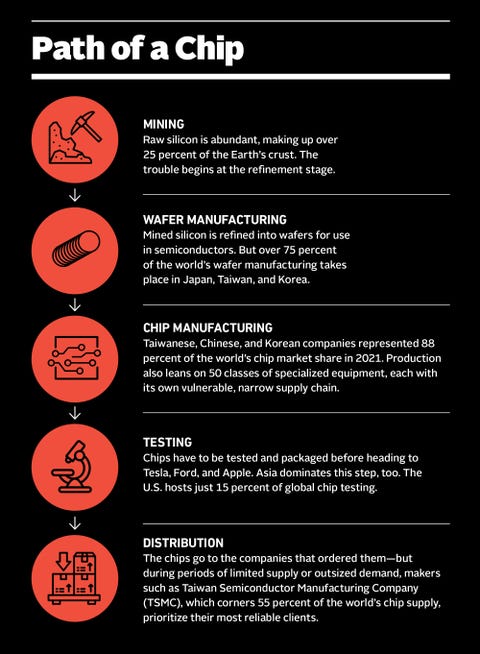

We can’t make modern cars without semiconductors—a.k.a. computer chips. And lots of them. As our vehicles have transformed into technologically endowed mobile offices, concert halls, and concierges, they’ve become mind-bogglingly complex. Chips tell the engine how much fuel and air to mix for maximum power and efficiency. They provide processing for our navigation and entertainment systems. They even help warm our seats to the right temperature. A decade ago, a Volkswagen vehicle had several hundred chips. Today, it might have more than 5,000.

These tiny microprocessors are like the ones operating our electronics, from iPhones and 4K TVs to home printers and gaming consoles. Though complex in design, the chips perform a relatively straightforward task: They act like electronic switches that create and obstruct pathways for electrical currents. That on-and-off flow of electricity allows chips to process inputs and store information, managing the thousands of complex actions we ask of our vehicles as we drive.

Prior to the pandemic, global chip producers supplied a steady stream of microprocessors to automakers. Despite the size and revenue of the world’s largest car brands (Toyota made about $280 billion in revenue in its latest fiscal year), automotive sales represented just a small portion of chipmakers’ business before COVID-19. Exponentially more iPhones are sold every year than crossover SUVs, despite the chip-hungry design of those vehicles.

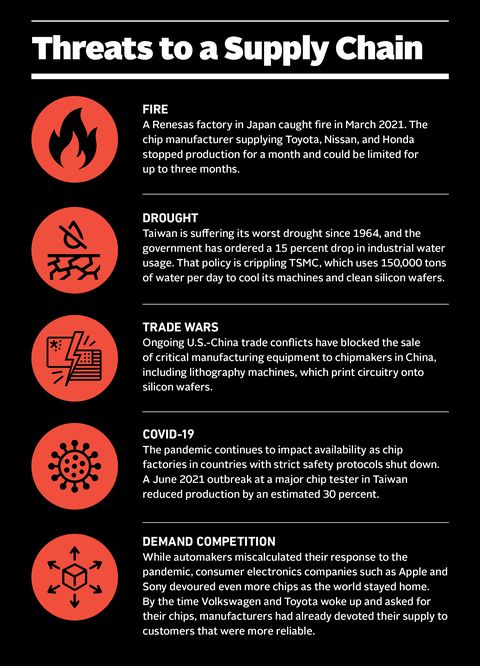

When the global pandemic arrived in the United States in the spring of 2020 and governments issued stay-at-home orders, factories that manufacture cars, suppliers that create components for cars, and car retailers shut down or greatly reduced their production levels. The manufacture and sale of new vehicles took a major hit. In fact, according to the International Organization of Motor Vehicle Manufacturers, global car production fell by an astounding 16 percent in 2020. In the U.S. it fell by 19 percent, part of a global decline that former OICA president Fu Bingfeng called “the worst crisis ever to impact the automotive industry.”

Believing they were about to enter a global recession, auto executives sought to alleviate a predicted glut of unsold inventory. They further scaled back production and canceled orders for parts, including computer chips. And when businesses reopened that spring and summer, automotive retailers slashed prices and offered deep incentives on new vehicles—including zero percent financing for 60-month loans—hoping to quickly move existing cars, trucks, and SUVs off dealer lots.

What happened next surprised almost everyone.

“Consumers raced back into the vehicle market,” Krebs says. People who had delayed purchasing a new car took advantage of these deals; according to data from Cars.com, more than 50 percent of buyers in the first year of the pandemic purchased a car sooner than they had expected to.

The exodus of people away from dense cities created new customers who needed vehicles to get around suburban and rural roads. Even those remaining in cities increasingly opted for personal vehicles over public transportation or ride sharing. Across the country the use of public transportation for work fell by 76 percent.

Then came federal stimulus checks, which fattened many bank accounts while restaurants, hotels, and shopping outlets remained closed. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that disposable income increased by $1.2 trillion in 2020, and that spending was concentrated on durable goods like furniture, appliances, and especially cars.

Hoping to increase production to meet demand, automakers attempted to reinstate orders for parts. But chipmakers, facing their own factory closures, had less inventory. Once work could continue, other industries’ needs for semiconductors took precedence over the automotive sector.

“Chipmakers were getting high demand for more profitable chips than those they make for the auto industry,” Krebs says. “[Mostly] from electronics makers trying to keep up with increased demand for laptops and phones and video games—since people were all working, and schooling, and entertaining themselves from home.”

The auto chips that did reach the end of the assembly line ran into their own problems as, among other things, dock workers in the global shipping industry were furloughed or quarantined. “The ports got clogged with ships,” Krebs says. “And chips were on those ships.”

Carmakers Get Stuck in a Supply-Chain Fiasco

It’s rare for an entire industry to miscalculate so badly. In the world of motorsports, this would be akin to running out of fuel on the last lap of Daytona, or F1 driver Max Verstappen speeding into pit row at Monaco to find his crew sitting there without fresh tires ready. Auto companies scrambled to increase production and sell more cars to eager buyers.

Some automakers, such as Tesla, rewrote the code on their available supplies of chips, rendering them usable for new car production. Others, like GM, opted to remove some chip-reliant features, like heated seats, from new vehicles in order to better distribute their limited number of chips.

Ford took a more aggressive approach with its most popular vehicles. Rather than wait for more chips to arrive, the company reportedly continued production of its Bronco SUV and F-150 pickup (the country’s best-selling vehicle for four decades), building both without the chips necessary to run them and stowing them in giant holding lots to await the availability of chips. Many of these inoperable vehicles still sit in those lots waiting for chips—four-wheeled versions of what the electronics community calls “a brick,” a gadget that through faulty componentry or spent batteries offers all the utility of a clay block.

Nearly all makers diverted what few chips they had into the production of their most valuable vehicles. “Automakers are putting what chips they have in vehicles that are in high demand, low inventory, and high profit,” Krebs says. “So you’ll see car plants closed down, while SUV plants and truck plants keep going.”

To wit, GM idled or reduced production at the plants that produce the Chevrolet Bolt electric hatchback, the Chevy Equinox, and GMC Terrain crossovers. Meanwhile, the factories that produce high-dollar full-size trucks and SUVs, and luxury vehicles like the Chevrolet Corvette and Cadillac CT4 and CT5 Blackwing, remain in full swing.

High demand combined with carmakers privileging the production of more-expensive models has helped drive the average new car price up 13 percent from two years ago, to nearly $47,000—an all-time high.

Independent dealers, sensing a tight market and trying to recoup some of their own losses, are engaging in price gouging, slapping markups on popular and desirable vehicles. These markups are often called “market adjustment fees.” At the time this article was published, a Ford F-150 was listed with a $9,995 premium at a dealer in Turlock, California; and several Corvette Z06 sports cars at a Chevy dealer in Clearwater, Florida, were listed with markups close to or more than $30,000 above MSRP.

Finding the Right Vehicle Amid the Chip Shortage Chaos

Many of the analysts and experts we spoke with say they see small signs of improvement in the market, but they expect the chaos to last for at least another year, or longer. Sabin Blake, a GM spokesperson, says the automaker has a more consistent supply of chips than it did at this time year ago, but it’s not enough yet to meet demand. “There is still uncertainty and unpredictability in the semiconductor supply base,” Blake says.

It’s a seller’s market, but car shoppers do have options. Autotrader’s Brian Moody advises car buyers to expand the types of vehicles they want. High demand for trucks, SUVs, and crossovers is keeping inventories low and prices high. That means there’s more value in other vehicle types. “You might have to look at something that’s less popular, like maybe a sedan, hatchback, or subcompact,” Moody says.

If you are set on a truck or SUV, you’re not completely out of luck. Brands like Ford have offered incentives to buyers who prepurchase custom-built models of trucks and other vehicles, taking $1,000 or more off the price for customers who reserve a vehicle with a down payment and are willing to wait a few months for delivery.

Prospective buyers can also look at less popular brands, especially for SUVs and crossovers. Companies such as Alfa Romeo and Hyundai have discounts on crossovers and sedans. A key to finding those deals is expanding your search area. Several popular models, including the RAM 1500 truck and Jeep Wrangler SUV can be found for just below MSRP. And in mid-May, several GM models, including the Chevy Blazer and Equinox, were listed at about 8 percent below MSRP. But many incentives apply to regional dealers and often only on vehicles with specific packages of options. A buyer may need to travel to another state to find the best deal.

“Instead of searching 25 miles away, try 500 miles,” Krebs says.

Car shoppers looking for new electric vehicles might have the hardest time. These vehicles require as many, if not more, chips as traditional cars, and their battery technology makes them more expensive than their internal-combustion counterparts. And with increases in fuel prices and wider acceptance of battery power, demand for EVs during the chip shortage has outpaced that of gas-engine vehicles. “Consideration of electric cars has doubled in the past year or two,” Moody says.

EVs and hybrids often have an advantage: They can be more reliable over more miles than gas-fueled alternatives. “The battery and drive components typically have a longer warranty than almost any car you can think of,” Moody says. These cars tend to depreciate faster than average, too, so you can (maybe) find a fair deal.

Moody advises shoppers who want a gasoline-powered vehicle to scour the used market. Although prices there have also increased—about 25 percent since last year, according to research from Cox Automotive—there might be more available options to choose from, especially for high-demand models. Because contemporary used cars are reliable and durable, he even suggests that shoppers expand their used-car search to include higher-mileage vehicles—with 100,000 miles or more on the odometer—as long as they also get the vehicle history report.

The best used-vehicle deal might be on the car or truck you already possess. If you leased a vehicle in the past few years, you can take advantage of rising used-vehicle prices by buying out your lease, even if it’s not yet due. Automakers and lenders didn’t anticipate the spike in prices when assigning a residual value—the amount you would pay to purchase the car when the lease ends—and those values may now be a steal. According to data from Edmunds, the average 2019 leased car is worth $7,200 more than automakers estimated. Due in part to those favorable prices, GM reports that for the first quarter of 2022, nearly all of its leased vehicles were purchased by customers or dealers when their terms expired. In 2019, only about 25 percent were purchased by customers or dealers.

Jessica Caldwell, the executive director of insights at Edmunds, offers another alternative: Extend the lease. Lenders may allow you to continue your current lease on a month-to-month basis or sometimes for a full year. That can buy you time to shop for a new vehicle or for prices to return to normal levels.

But even after the chip shortage ends, some of its effects are likely to persist. “I don’t think we’ll see automakers and dealers going back to overproducing and slapping on big incentives,” Krebs says. “They’ve realized that keeping production a bit lower than demand is highly profitable.”

The best advice, then, might be this: If you can find a fair deal on a new or used vehicle that meets your needs, grab it.